The rise in energy costs caused by Europe’s move away from Russian gas will make for a challenging winter as high inflation pushes the region’s economies towards recession.

Europe has prepared well for higher winter energy demand with gas stocks close to full.

While domestic gas markets may still come under intense pressure if temperatures fall sharply in early 2023, beneath all this, something has been lost in the wider narrative: The resilience of Europe’s wholesale energy markets, and their ability to function effectively despite the loss of almost 30 per cent of baseload gas supply, has been remarkable.

Cooperation

The EU’s energy legislation, pushed forward over the course of 20 years, has fostered cooperation between member states alongside competitive internal markets with energy supply unbundled from transmission.

The EU’s design principles, which also hinge on benchmark price signals that indicate where energy should flow and what actions market participants should take, have ensured nations have generally been protected from blackouts or the loss of supplies.

In fact, if the EU’s principles around removing bottlenecks had been fully addressed across every member state, then at least some of the current regional pressures and imbalances would have been less severe, especially in parts of south and eastern Europe.

Price cap?

It is unsurprising that some of those European countries now most dependent on attracting LNG to replace missing piped gas are those that have spoken against the introduction of a wholesale price cap on the regional benchmark, the Dutch TTF.

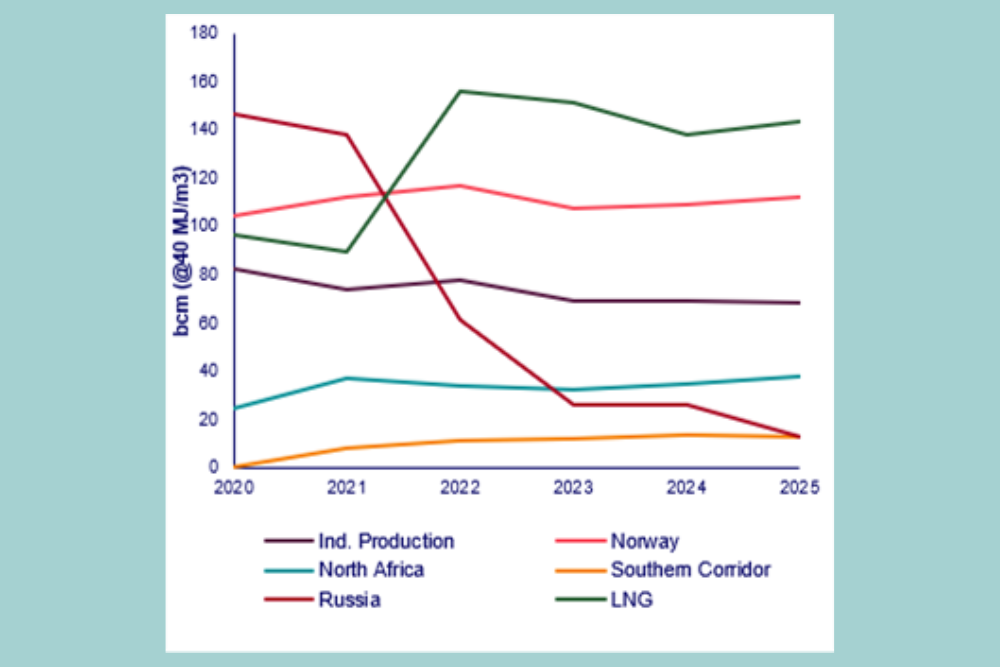

Germany is the most obvious example. It will need to pull in large volumes of LNG to replace Russian gas, and this can only be done with responsive pricing which may be frustratingly high, but without which cargoes will simply head to other global markets.

The huge, immediate investment in new European LNG import infrastructure is another reflection of how responsive these markets are to pricing and supply signals.

The issue, of course, is that there simply is not enough global supply available with the result that TTF prices have risen to record highs.

But without effective wholesale energy markets, Europe would not be in a position to attract the cargoes it requires.

And it is those price signals that have led to a load of laden LNG vessels just waiting to supply into European markets over the winter.

TTF prices have fallen by over 63 per cent from the record highs of just a few months ago with the market taking steps to mitigate the end of Russian Nord Stream flows.

This is both a strong example of how responsive prices are to supply and demand fundamentals but also a warning over the risks of interfering in functioning wholesale prices which are increasingly connected with global markets: price signals are required both to respond and to prepare.

Swift support

European resilience has also stemmed from swift government support for ailing energy buyers and a mandate to fill storage. Together such steps have provided reassurance ahead of the winter.

Other parts of the world are in a less fortunate situation, with regulated domestic energy prices in some cases so far below wholesale import costs that governments are increasingly unable to bridge the financial gap. Energy blackouts are a common result in parts of South Asia, for example.

While very high energy prices are rippling through European economies through widespread cost inflation, in turn leading to interest rate hikes, they also ultimately trigger the kind of demand destruction that serves to balance the market.

All of this is a result of cutting a vast chunk of European gas supply with almost no notice, rather than any failing of underlying market structure.

There are numerous examples of failed markets or where intervention has caused damage, even in more evolved markets such as the US.

Back in 2000-2001, caps on retail electricity prices and manipulation of opaque markets fuelled a two-year energy crisis in the western US that resulted in rolling black-outs, a series of scandals and the bankruptcy of a number of the region’s most important energy utilities including PG&E and Enron.

The energy price caps, combined with manipulation of the wholesale market to force a higher wholesale price, squeezed revenue margins and tipped producers into liquidation. The ultimate cost of this market failure was estimated at more than US$40 billion dollars.

In years to come economists and regulators would blame a lack of investment, delays on new power plant approvals, perverse incentives, poor regulation and ill-judged political intervention as the root causes.

And 20 years later, three predictable winter storms left the worst energy infrastructure crisis in Texas state history in their wake, cutting off electricity from more than 4.5m homes and businesses. At least 250 people were killed officially, with the unofficial number far higher.

A failure to prepare energy infrastructure for the winter months was blamed, alongside an inability to import from neighbouring states due to a lack of investment and connections.

This was all ultimately an unintended consequence of 1990s deregulation and a competition-driven race to the bottom on price.

Europe, 2022

Compare these catastrophic market failures with Europe so far in 2022.

Infrastructure capacity limitation has proved the only barrier to the free flow of energy.

There are still challenges to come. The gas pipeline system, built to transport energy predominantly from east to west, must now perform an about-turn.

But a long list of new LNG import terminals is already under development, with the first new terminal in the Netherlands regularly seeing cargoes delivered.

Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine has exposed many things: a failure of diplomacy even as troops massed at Ukraine’s borders, the fragility of global supply chains and the danger of Europe’s historic over-reliance on Russian gas.

But the ability of Europe’s market design to deliver secure energy supplies to millions of consumers under the most testing of circumstances should be recognised as a rare positive.

Perhaps the greatest test of any winter is yet to come, and with a difficult summer to follow that.

But the European energy market model has, so far, delivered. Even in the most challenging of circumstances.

Additional reporting by Jamie Stewart, Managing Editor, Energy, ICIS.