Disruptions to Red Sea LNG traffic stepped up over the weekend as Qatar, the biggest single user of the route in 2023, paused several vessels due to cross through the Bab al-Mandab strait.

The narrow passage, at the bottom of the Red Sea, has become the centre of global attention over recent weeks after Houthi attacks on shipping crossing the strait, followed by US and UK counter-strikes at the end of last week.

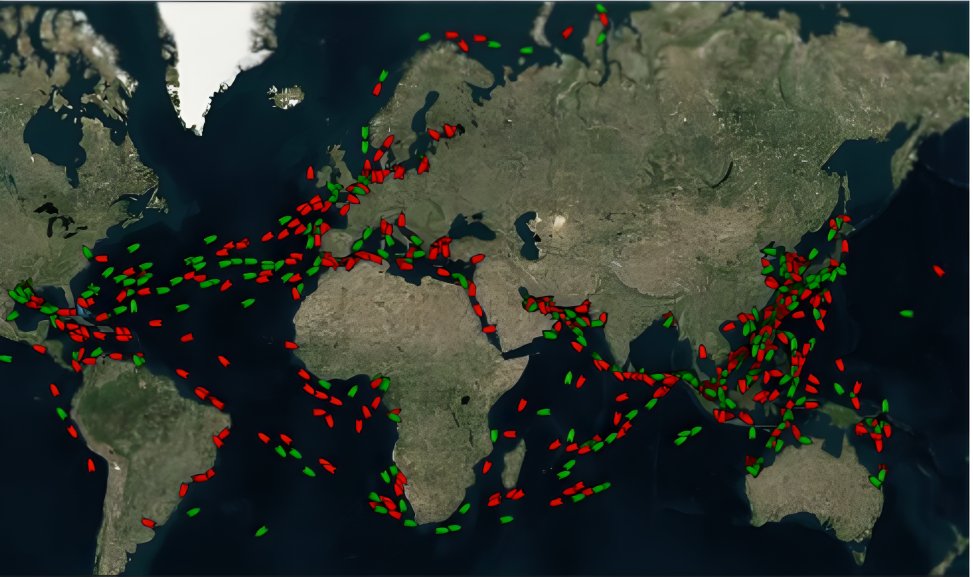

ICIS LNG Edge shows three laden Qatari tankers — green, and one ballast — red, pausing.

Three laden Qatari tankers that were signalling a course to the Suez Canal cut their speed on Sunday 14 January and started circling off the coast of Oman, east of the strait.

The Al Ghariya, Al Huwaila and Al Nuaman seemed to be waiting to decide whether to head west through the strait into the Red Sea or instead to divert south to head around Southern Africa to Europe.

The tankers were all likely heading to Europe, possibly to a long-term contract customer of Qatar such as Italy or Poland, or to make a spot delivery to Qatar’s UK terminal position.

Heading down around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and then back north to Europe would take around 27 days to reach the UK, compared with only 18 via the Red Sea and Suez Canal route.

Qatari ships have been seen taking this longer route before, but very rarely.

*Routes from ICIS LNG Edge shipping calculator.

The ballast Qatari tanker Al Rekayyat, which was returning to Qatar, cut its speed on 13 January and is now paused in the middle of the Red Sea.

The tanker had crossed through the Suez Canal but had not yet reached the Bab al-Mandab strait.

Qatar supplied Europe with 16 per cent of its LNG imports during 2023, equal to around 15.1m tonnes of the region’s total 96.2m tonnes.

That made Qatar a key supplier to the region, although significantly lower than the US, which made up almost half of Europe’s LNG supplies in the year at 45.5m tonnes.

Disruptions to Qatari LNG flows to Europe could add time and costs to deliveries, likely lifting spot gas prices.

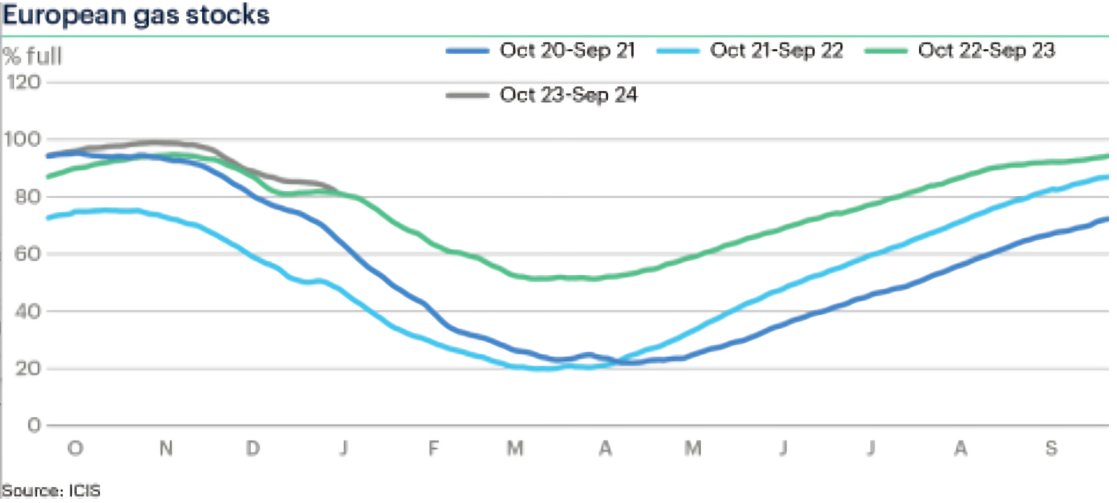

However, Europe is well placed to deal with disruptions, with its gas storage still very high for the time of year, and much better positioned than two years ago when Russia started its war with Ukraine.

Non-Qatari LNG moved first

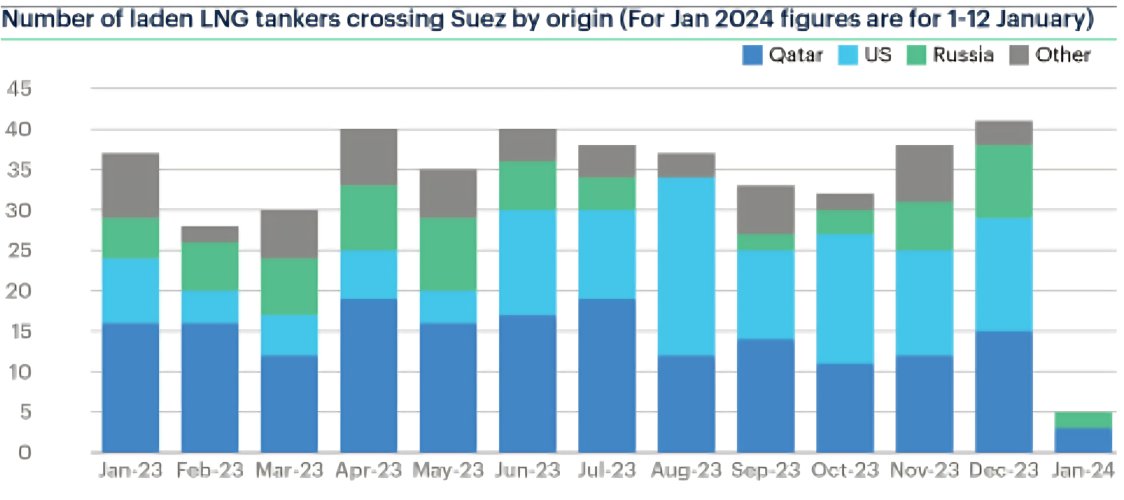

ICIS LNG Edge tracks the movements of LNG ships around the world, normally seeing around 30-40 laden LNG tankers crossing through the Red Sea each month. ICIS counts the tankers as they pass the Suez Canal at the top of the sea.

Tankers would also cross the Bab al-Mandab strait at the bottom of the sea.

Qatar was the single biggest user of the canal for LNG cargoes across 2023.

Russian-origin cargoes from the Arctic Yamal LNG plant also head south through the Red Sea to deliver to customers in China.

The US has also often used the canal to deliver cargo to Asia, sending them east across the Atlantic, then through the Mediterranean and down through Suez.

Routes east from the US to Asia have become more important in recent years as the Panama Canal has grown more congested and suffered from drought, reducing water levels.

The number of crossings in December was fairly in line with normal.

ICIS did see some cargoes avoiding the Suez Canal that month, so the strong figures in December may reflect the fact that there was a greater number of US cargoes heading east to Asia in total, due to strong Asian gas prices and the Panama Canal being busy.

There was high demand, even as some ships started to divert away.

During January 1-12, 2024 however only five laden LNG tankers were tracked through the Suez Canal, and all of these were either Qatari or Russian cargoes.

The last non-Qatari or Russian cargo through the canal was the Flex Volunteer, which crossed Suez around 30 December and passed through the Bab al-Mandab strait around 3 January, on its way to deliver a US Calcasieu Pass cargo to Pakistan.

Some US spot cargoes may now look for shorter routes to Europe rather than the long route to Asia, while other US cargoes are building up traffic on an increasingly busy route southeast across the Atlantic and around the Cape of Good Hope to Asia.

For US cargoes heading to Asian customers such as China, Japan and South Korea, taking the route via the Cape of Good Hope only adds a couple of days compared with heading via the Suez Canal, although it is significantly longer than heading west via the Panama Canal and across the Pacific.

It was not unusual before the recent Red Sea disruption to see some US cargoes taking the Cape of Good Hope route, although many others took a route via the Mediterranean and the Suez.

The Mediterranean route also offered optionality to divert sales to Europe.

When US cargoes were avoiding the Red Sea, but Qatari cargoes continued to use it, the overall disruption to LNG traffic seemed less significant than to general cargo traffic, where a lot of container ships are travelling from Asian producers such as China back to Europe via Suez and face significantly longer routes if they divert around the Cape of Good Hope.

However, if Qatari cargoes now stop using the Red Sea, this would raise the impact on LNG traffic significantly.

Market Impact — Mitigation

It remains to be seen if Qatari ships will stop using the Red Sea long-term. As of 15 January, the vessels had paused but not decisively moved south to the Cape of Good Hope route.

There is no immediate threat to Europe’s security of gas supply as the region is well stocked with gas and has steady inflows of other gas, including Norwegian pipeline gas and US LNG.

For much of the first half of winter, the weather has been relatively mild and industrial demand remains suppressed from pre-crisis levels.

However, if Qatari ships needed to take much longer routes long term, this would add to costs and be a bullish influence on spot gas prices, although at a time when they have already fallen sharply over recent months.

The conflict in the Middle East is also bullish for oil prices, which can have an impact on the gas market, as many long-term LNG contracts in Asia are linked to oil prices.

Although Europe’s spot prices at the ICIS TTF have fallen hugely from the records broken in 2022 when Russia halted most pipeline supplies to Europe, even now gas prices remain above the long-term averages in the decade before the Russia-Ukraine war, adding to bills for households, leading to factory closures and challenging inflation targets.

In the event of long-term disruption, energy companies could attempt to re-arrange global trade flows to make shipping more efficient.

For example, a US company that had to deliver cargo to Japan could swap with a Middle Eastern company that wanted to sell into Europe.

The US company could deliver its cargo into Europe instead and the Middle East customer could deliver east into Asia.

Both customers would receive a cargo, and overall shipping times would be cut. In this case, both companies might avoid any need to use the Red Sea at all.

Companies already carry out such swaps internally and from time to time with other parties.

For a major LNG trading company like Shell or TotalEnergies, the ability to re-arrange flows in such a way is one of the benefits of having a large global trading portfolio that they can find cost savings within.

However, while it could be a theoretically attractive way to minimise the fallout from any prolonged shipping disruption, in practice to do this on a very large scale between major companies would require an unprecedented new level of trading and cooperation.