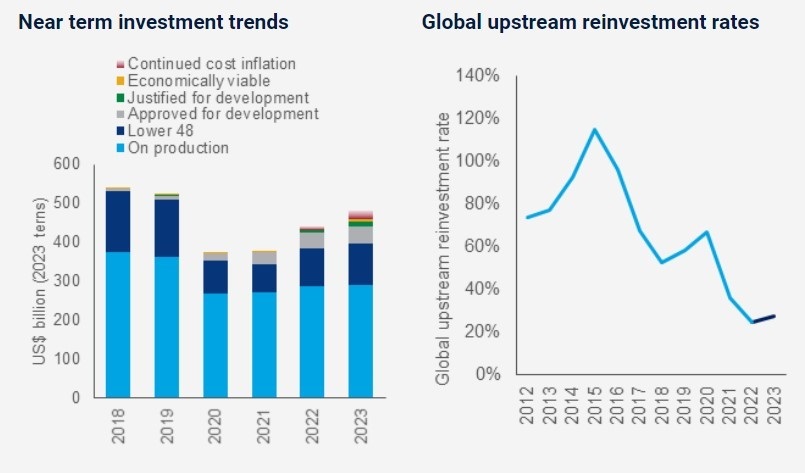

The energy transition will require oil and gas for decades to come, but the supply of lower-cost, lower-carbon “advantaged” barrels remain scarce, threatening emissions targets and causing upstream providers to pivot to new strategies, according to new analysis from Wood Mackenzie.

The analysis concludes that in terms of overall supply, total discovered and prospective oil and gas resources are more than double projected demand in 2050.

However, truly advantaged resources, with low breakeven (resilience to low prices) and emissions (sustainability in scope 1 and 2 terms) are anything but plentiful.

Most developed fields have little to offer and only 28% of the resources in commercial undeveloped fields, roughly 49 billion barrels of equivalent (boe), are advantaged in terms of breakeven below US$30 Brent with emissions intensity of less than 20 kgCO2e/boe.

“We see enough advantaged resources to satisfy only about half of our base-case oil and gas demand forecast to 2050,” said Andrew Latham, vice president, Energy Research for Wood Mackenzie Upstream.

“Even our much lower AET-1.5 demand scenario – which lays out what is needed to achieve the most ambitious targets of the Paris Agreement by keeping emissions within 1.5 °C of pre-industrial levels and reaching global net zero by 2050 – will require some disadvantaged supply.”

Under Wood Mackenzie’s base Energy Transition Outlook (ETO), oil demand peaks in 2030, before declining slowly to 94 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2050.

The AET 1.5 requires 20 million b/d lower than the ETO by 2035, but will still be 33 million b/d by 2050.

Under the ETO scenario, gas demand will be 88 million boe/d in 2050, some 12% higher than today.

Under the AET-1.5 scenario, gas demand in 2050 will fall to 59 million boe/d.

New exploration, decarbonization technologies and biofuels deliver some relief

With few advantaged resources in brownfields and undeveloped fields, exploration could play a key role in locating and increasing this supply.

The industry discovered 228 billion boe in new fields between 2012 and 2021, with an average emissions intensity of 16 kgCO2e/boe, versus the current global average of 23 kgCO2e/boe (19 kgCO2e/boe for undeveloped fields).

And with a weighted average cost of supply in Brent price terms of just US$33/bbl.

Latham added: “We expect high-impact exploration to be an important source of new resource for as long as demand remains at or near our ETO trajectory.

“Recent results suggest a contribution of around 5-10 billion boe of new advantaged barrels a year.

“Most will be found within energy super basins.

“Exploration on this scale over the next two decades will add oil and gas supply of around 10-15 million boe a day by 2050.”

Decarbonization technologies and biofuels could play an even bigger role.

Bio-based diesel and aviation fuels from plant-based feedstock could emit 80% less carbon than the crude oil-based products that dominate today’s oil market.

Wood Mackenzie projects up to 20 million b/d being possible by 2050.

“This is really a wake-up call for the industry and for the overall energy transition outlook,” said Latham.

“These are avenues that help alleviate advantaged supply pressures, but it is definitely going to be an uphill struggle.”

A difficult road ahead for upstream sector

While these strategies may help, it will become much more difficult for companies to find and produce the advantaged barrels needed to meet base ETO demand.

Latham concludes that it would be very difficult for advantaged resources alone to meet all ETO oil and gas demand: “We are entering an interesting period in the upstream industry.

“Some companies will double down and hope for less competition in the sector.

“However, many may begin or accelerate their exit from the sector to pursue low-carbon energies and renewables.

“If this is the case, security of supply may become threatened, and, unfortunately, we may see companies turning to disadvantaged resources to meet demand.”